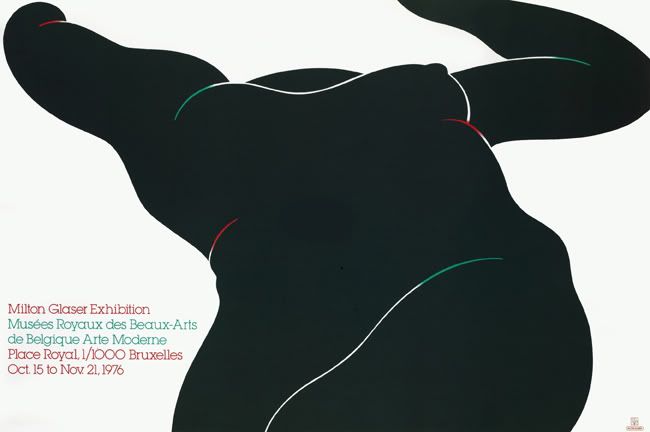

last year

i was

blessed

with the

chance to

interview the

godfather of

graphic design

Milton Glaser.

I understand you grew up in a progressive part of the Bronx at the beginning of The Great Depression. How did this environment impact you philosophically and can you speak to how your life experience there led to becoming an artist at such a young age?

I have no idea why anyone wishes to become an artist. I do know that at the age of 5, I made a decision to spend my life making things and I have never deviated from that objective. The motivation to see the world from the left or right philosophically is buried in the mysteries of the mind, although I find a liberal bias is more prevalent in artists. I associate liberalism with an open mind, which includes the possibility of one's being wrong. A characteristic of the right is 'certainty', which certainly inhibits the imagination.

One more nice fact to recall: 95% of the kids that grew up in my neighborhood went on to college.

After finishing your high school education, you were denied entrance to Pratt. Do you think, in retrospect, that not getting in was perhaps a blessing in disguise?

Perhaps. Altered plans frequently turn out to be blessings. And remember, not only did I fail the Pratt entrance examination, I also failed the Pratt nightschool examination. I'm probably the only student to ever fail the nightschool examination. After my double-flunking, and since I hadn't applied for any other college, I went to work at a package design studio. A year later, I went on to Cooper Union. The little bit of professional experience I got from the design studio gave me slight edge over the other students.

You were one of the founding members of Pushpin Studio. How did Pushpin originally come about?

Pushpin came about because Ed Sorel, Seymour Chwast, and Reynolds Ruffins and I were fellow students at Cooper Union. While there, we started a small company called Design Plus, whose sole activity was printing cork place mats. After finishing our schooling, we went our separate ways until we reunited in 1954 to start Pushpin Studios. I suspect it was the pleasure we found working together that made us want to recreate that experience as professionals. (Although by any standard, we were far from professional.)

When you started publishing the Pushpin Almanac was it a labor of love or a really clever way of attracting new clients? or a bit of both?

I was in Europe on a Fulbright when Reynolds, Ed and Seymour created the Almanac It was their way of communicating with other designers (and possible clients). The Almanac broke away from prevalent modernist vocabulary,and integrated design, typography and illustration in a fresh way. When I got back from Europe in 1954, I joined the others and, based on the success of the almanac, we decided to open Pushpin Studios.

When teaching, how do you connect ethics to applied arts for your students?

For me, there's no way of teaching design without engaging the relationship between design and ethics. This means that in creating a work that communicates to a public, the artist must include the question, "What are the consequences?" If this question is not considered, design becomes simply a way to create an ideology or make money.

What major changes have you seen, through time, in applied arts in regards to ethics and to what do you attribute this?

It's difficult to discern what real changes have occurred. Certainly there is a significant amount of lip-service given to design and its social effect. As a result it has become more trendy to be concerned about these issues. I say this not disparagingly because in our culture, when things become trendy, they frequently produce change.

What advice would you give to young graphic designers with respect to maintaining artistic integrity within the commercial spectrum?

What do we mean by artistic integrity? Do we mean persisting in our ideas even though they may be demonstrably wrong-headed? Do we mean that despite a client's concerns, we act as though the only solution is the one we have decided on? Is there a difference between artistic integrity and egocentricity? On the other hand, if the question becomes, "Is harm being done?" the issue becomes somewhat simpler.

For a period of time the computer was king in graphic design. However, there seems to be a return to pen and paper. What do you feel has brought about this shift?

I love the computer. But I'm convinced only people over 40 should be allowed to use it. The problem with the computer is that it is too powerful a tool for inexperienced people to use. That's because, if you have not already developed your sense of form through the arduous experience in making things, the computer will impose its will on you. It, and not you, will determine your sense of size, scale, color and value. Soon, everyone noticed that every job produced on the computer tended to look alike. And that was probably because inadvertently, every designer began thinking in terms of what the computer was most comfortable creating. This is as insidious as it is inevitable. The shift back to pen and paper came about because people realized that any designer's sense of form is won through frequent repetition of the relationship of the eye to the brain to the hand. There is no better way of developing aptitude.

Along with Picasso and Morandi, you have said that William Morris has been an influence on your work. Who, or what, has been the biggest influence on your aesthetic?

I remain fascinated by the relationship between Morandi and Picasso. Picasso was a man who wanted everything, every style, every medium, all the money, all the women, all the fame. His work is full of virtuosity, interesting narratives, enormous scale, and overwhelming success as seen by the public.

Morandi was a man who wanted nothing. He didn't travel, he lived alone with his three sisters, his paintings were small and without narrative, his use of color was subdued and underdramatized. The work seemed without virtuosity or impressive technique.

So here's the question: In a contest between these two extraordinary polarities, who wins? In my perception, it's a toss up. The result of this perception is my realization that the things we believe are important in works of art may be illusionary and, when it comes right down to it, 'tain't whatcha do, it's the way thatcha do it.

Over the years it seems, many of the decorative, descriptive elements of your work have fallen away and yet it remains very narrative. Was this the result of a process or natural progression?

Isn't natural progression a process? Yes to both.

Do you still feel nervous when you submit your work to a client?

I don't think so.

After all this time, what keeps you inspired and motivated?

First, the idea that I might learn something new that day. Second, working with the delightful people in my studio. Third, what else could I possibly be doing?

photo: Molly Watman

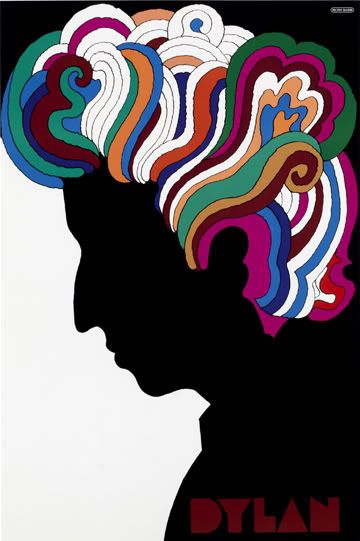

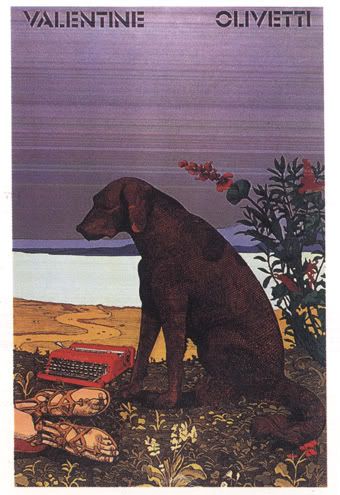

all images used by permission

from Milton Glaser Inc.

No comments:

Post a Comment